In Friday’s column, I explained that “What do you think the market will do next?” is a bad question because there is no good answer.

No one – not Warren Buffett, Ken Fisher, Jerome Powell or anyone else – knows what the market will do next.

Yet there is a good living to be made – both on Wall Street and in the prophecy racket (also known as the investment forecasting business) – pretending to know.

The more specific the forecast, the faster you should run.

For instance, “The market is likely to find support soon and then rally from here” is meaningless and mildly amusing.

However, “Expect the Dow to rally to 25,720 and then decline to 24,215 before exceeding its record closing high of 26,828” is a true knee-slapper.

The folks who make these pronouncements make a lot of money. The folks who follow them? Not so much.

As I mentioned in my last column, sophisticated investors focus not on unanswerable questions but on what they can actually control.

For example, here are the seven factors that will determine the future value of your portfolio:

- The amount you save

- The length of time you let it compound

- Your asset allocation

- Your security selection

- Your sell strategy

- The expenses you absorb

- The taxes you pay.

You cannot control GDP growth, inflation, interest rates, Fed policy, or what the market or individual securities do from day to day – or year to year.

But you can control every one of the seven factors above.

If you want to reach financial independence sooner, save as much as you can. Let those monies compound as long as you can. Asset allocate properly. Choose your securities wisely. Follow a disciplined sell strategy. Cut your investment costs to the bone. And tax-manage your portfolio to minimize state and federal taxes.

I could write a book on each of these topics, but let’s stick to just one important factor today: asset allocation.

Studies consistently show that your asset allocation is your single most important investment decision. It is responsible for up to 90% of your portfolio’s long-term return.

Asset allocation refers to how you diversify your portfolio into different noncorrelated asset classes, like stocks, bonds and cash.

(“Noncorrelated” means that not everything in your portfolio will move in the same direction at the same time. When some securities zig, others will zag.)

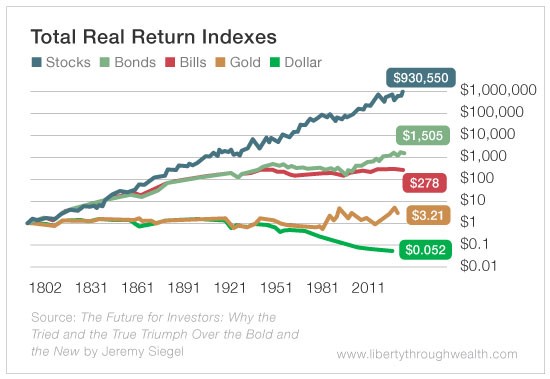

History demonstrates that nothing comes close to matching the long-term returns of a diversified portfolio of stocks.

If you have any doubts, take a gander at the chart below.

Every dollar invested in common stocks over the past two centuries is worth over a million dollars today. And that’s on an inflation-adjusted basis. Nothing else comes close to delivering this kind of return.

So if you want to boost your future long-term returns, increase your stock allocation. (And expect greater volatility, since stocks fluctuate more than bonds.)

Conversely, increasing your bond allocation will smooth out the bumps but lessen your future returns.

Why would anyone act to reduce future returns?

Because they realize they don’t have the stomach to endure protracted downturns.

Like me, you probably know plenty of people who cashed out of stocks in the recent financial crisis and either got back in much later or never got back in at all.

People are not unfeeling automatons. When markets decline – and folks start remembering that this is real money that has suddenly (if temporarily) gone “poof” – they want to do something.

And that something is generally to sell to the sleeping point.

If you’re one of these folks, take a look at your asset allocation and make the necessary adjustments now.

How?

Pull out – or print out – all your most recent bank, brokerage, mutual fund and retirement account statements. Total up these liquid assets and determine what percentage is in stocks and what percentage is in bonds.

If, for instance, your portfolio is worth $200,000 and you have $126,000 in stocks and $74,000 in bonds, your asset allocation is 63% stocks and 37% bonds.

Now vividly imagine that a ferocious bear market knocks stock values down 50%. Could you live with a temporary decline of $63,000 in your portfolio’s value – without selling in a panic to “cut the losses” or “lessen the pain”?

If not, make your portfolio more conservative now.

On the other hand, if you have ridden out down markets before or – better still – used them to pick up additional assets on the cheap, feel free to maintain or even increase your equity allocation.

In general, the younger and more aggressive you are, the more you should have in stocks. (In fact, it makes sense for young children and grandchildren – who don’t even know or care what their monthly statement says – to be 100% invested in equities.)

If you are older and more conservative, you’ll want to have less. Although in my opinion – and that of Benjamin Graham (Warren Buffett’s mentor) – almost no one should hold less than 20% in equities.

Long-term investors have no good reason to fret about what the market will do next.

And if you want to ask a qualified investment professional a good question, make it this: “Hey, would you mind taking a look at my asset allocation?”

Good investing,

Alex