On the morning of April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. slept late. That afternoon he joked with his companions, taunting them into a pillow fight in his motel room.

An hour later, he stepped onto the balcony of his room and paused a second, trying to decide whether to take a jacket.

From a window 200 feet off to his right, James Earl Ray brought the crosshairs of his rifle sights onto King’s neck and squeezed the trigger.

It was the end of a life… and the beginning of a powerful legacy.

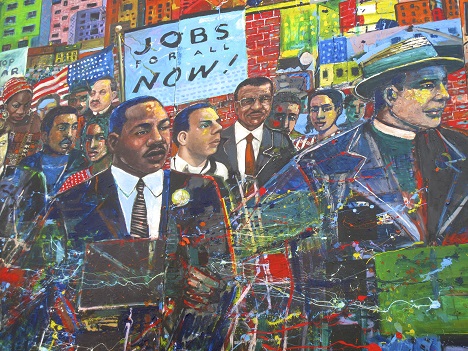

This week millions of Americans will pause to remember and celebrate the life and achievements of Martin Luther King Jr., the 20th century’s most influential civil rights activist.

King spoke passionately, wrote persuasively, and led countless marches and sit-ins, crying out for justice for oppressed minorities in the United States.

In January 1964, Time magazine named him 1963’s Man of the Year.

Later that year, King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize at 35, making him the youngest Peace Prize winner ever.

In 1977, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Like Jefferson and Lincoln, King was unequivocally the right man in the right place at the right time.

It wasn’t just that Black people were systematically denied equal rights and opportunities. There were the daily humiliations as well.

As a boy in the Deep South, King was regularly shooed away from white stores, white restaurants, white bathrooms and white water fountains.

On a long return bus trip from a debating contest, he and his teacher were told to stand so that white passengers could sit.

In a downtown department store, a matron once slapped him, complaining, “The little n—– stepped on my foot!”

King later recounted that he became determined to hate every white person. But his father, a Christian minister, taught him otherwise.

Though he too chafed at the indignities…

When his father was stopped by a traffic policeman who addressed him as “boy,” the senior King pointed to young Martin on the seat beside him and snapped, “That’s a boy. I’m a man.”

On another occasion, the two were told by a shoe clerk that Black patrons could only be served in the rear of the store.

His father grabbed the boy’s hand. “We’ll either buy shoes sitting here or we won’t buy any shoes at all.”

America was two societies, separate but unequal.

Yet King became convinced that racial hatreds were driven not by individual convictions but by attitudes deeply ingrained in society.

He made it his mission to change those attitudes. And he insisted it could only be done without violence.

His commitment to peaceful change came from three primary sources.

The first was the Gospel.

The second was Henry David Thoreau’s theory of nonviolence, famously articulated in his essay “Civil Disobedience.”

The third was the nonviolent thoughts and actions of Mohandas Gandhi with his strikes, boycotts and mass marches against British colonial rule.

Following these examples, King urged his followers to stand up to taunts, threats and harassment – as well as clubs, police dogs and water cannons – with peaceful resistance. It wasn’t easy.

One evening, a bomb exploded on the front porch of his house, wrecking the front parlor.

King rushed home to find his wife, Coretta, and their infant daughter safe in a back room.

However, the yard and street were filled with an angry crowd of more than 300 people, many armed with guns and knives.

Sirens wailed. Skirmishes broke out with the police. Reporters and onlookers pressed in, adding to the pandemonium.

Standing on the shattered glass and rubble of his front porch, King raised his hand and shouted, “We are not advocating violence!… I want you to love our enemies. Be good to them, love them and let them know you love them.”

To King, forgiveness was not an occasional act. It was a permanent attitude.

Today he is best recognized for his civil rights activism. But the Baptist minister really fought for something more.

His goal was nothing less than the moral reconstruction of American society.

He became an outspoken opponent of the war in Vietnam. Black Americans were disproportionately serving and dying in the conflict and, in a television interview, Mike Douglas asked King whether his opposition to the war might be misinterpreted.

King replied that he hoped not, since he opposed any American fighting and dying in a senseless war.

Watching film clips of Dr. King recently, I marveled again at his courage and intellect, his calm demeanor, his sense of hope.

Martin Luther King Jr. insisted that we all have an amazing potential for good, that there exists in each of us a natural identification with every other human being.

And that when we diminish others, we diminish ourselves.

Carpe Diem,

Alex