Americans recognize 1776 as the year the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence on the fourth of July.

But there is another reason readers of Liberty Through Wealth should recognize 1776 as a turning point in history…

On March 9, 1776, the 1,000-page, two-volume work titled An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations was published in London.

Economist and Liberty Through Wealth contributor Mark Skousen calls The Wealth of Nations “the intellectual shot heard around the world” and “a declaration of economic independence.” Its publication also marked the birth of modern economics.

The usually acerbic H.L. Mencken wrote, “There is no more engrossing book in the English language.”

University of Chicago economist and later Nobel Prize winner George Stigler called Adam Smith’s model of competitive free enterprise presented in The Wealth of Nations “the most important substantive proposition in all of economics.”

English historian Henry Thomas wrote that in terms of ultimate influence, The Wealth of Nations is “probably the most important book ever written,” including the Bible.

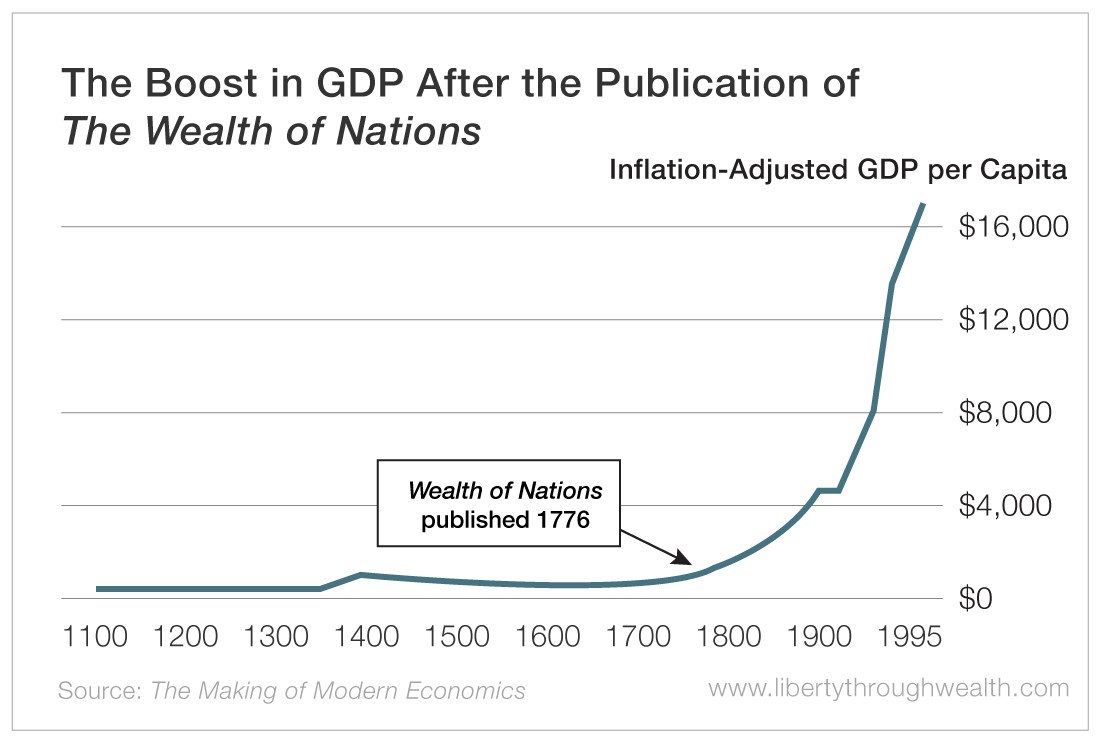

If that assertion seems like an exaggeration, consider the chart below.

Humanity generated next to no economic wealth before 1776.

But almost immediately upon the publication of The Wealth of Nations, the world saw both political and industrial revolutions explode onto the scene. This resulted in an era of unprecedented economic growth and wealth generation over the next two centuries.

Who Was Adam Smith?

Adam Smith was a quiet, absentminded professor who taught moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow. As a child of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith was friends with the great and the good of his era, including philosopher David Hume.

By all standards – even those of a Scottish culture that embraced eccentrics – Smith was an oddball. As the French novelist Madame Riccoboni wrote upon meeting Adam Smith in 1766, “He speaks harshly with big teeth and he’s ugly as the devil.” She later declared, “He’s a most absent-minded creature but also one of the most lovable.”

As Smith – who remained a lifelong bachelor – himself put it, “I am a beau in nothing but my books.”

Smith remained somewhat mysterious to his friends throughout his life. He famously had all of his unpublished work burned before his death. His friends agreed to his wishes and destroyed 16 volumes of manuscripts without knowing or asking about their contents.

Smith was reportedly greatly relieved.

The Wealth of Nations

In writing The Wealth of Nations, Smith had two primary objectives…

First, he set out to criticize the then-current and widely accepted economic model of mercantilism.

Second, he wanted to present his alternative economic system based on “natural liberty.”

As the chart above confirms, the world achieved little economic progress over the centuries in England and Europe during the reign of mercantilism.

Mercantilists believed that the overall wealth of the world economy was stagnant and a nation’s wealth was fixed. That meant a nation grew only at the expense of another. Economic wealth was a zero-sum game.

As such, mercantilists argued that wealth accumulation was based on the hoarding of gold and silver. This explained why governments authorized state monopolies at home and promoted colonialism’s aggressive focus on seizing gold and other precious commodities abroad.

Smith forcefully rejected the mercantilists’ definition of economic wealth.

Instead, Smith argued that the key to “the wealth of nations” was “production and exchange.”

As Smith wrote, “The wealth of a country consists, not in its gold and silver only, but in its lands, houses, and consumable goods of all different kinds.” In other words, wealth should be measured not by how much gold and silver a government has stored in its coffers, but by how well its people are lodged, clothed and fed.

Specifically, Smith replaced the theory of mercantilism with a model based on a “system of natural liberty.”

On a personal level, it implied the freedom to do what one wishes without interference from the state.

On an economic level, it meant the free movement of labor, capital, money and goods.

Smith highlighted three characteristics of this self-regulating classical model of economics.

- Freedom: the right to produce and exchange products, labor and capital

- Self-interest: the right to pursue one’s business and appeal to the self-interest of others

- Competition: the right to compete in the production and exchange of goods and services

Smith argued that these three ingredients would lead to a “natural harmony” of interest between workers, landlords and capitalists. The voluntary self-interest of millions of individuals created a natural stability without the need for central direction by the state.

This doctrine of “enlightened self-interest” is often called “the invisible hand.”

Smith was also the first to introduce the idea of “the division of labor” into economics, as well as the right to buy goods from any source (including foreign products) without the restraint of tariffs or import quotas.

Finally, Smith was a great optimist about the future. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith argued that his system of natural liberty would produce “universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people.”

In short, the ideas of Smith and The Wealth of Nations represent many of the beliefs and values we embrace here at Liberty Through Wealth.

And I’ll be writing more about these ideas and values – as well as the thinkers behind them – in future columns.

Good investing,

Nicholas

P.S. If you want to learn more about Adam Smith and the ideas and lives of other great economists, I highly recommend you read Mark Skousen’s excellent book The Making of Modern Economics.