- We’ve seen a lot of market volatility over the past week or so, but it’s not productive to worry about the present.

- As Matthew Carr explains today, looking to the future is a much savvier investment strategy.

I live in the future.

I’m constantly focused on tomorrow… or six months from now… or further out.

I’m not worried about today. I focused on today yesterday.

So the present is largely meaningless to me, as I’ve already penned my game plan.

This is why I’m not fazed by volatility or sell-offs. They’re opportunities to me and always have been.

When shares of companies fall 10% or more during a market downturn, it’s a gift. Because those shares will be higher a few months from now… maybe even a few days from now.

Broad market collapses – like the one we recently saw – are often steep and swift. But moves higher last far longer, with massive gains to be won.

That’s why the future always has more weight than the present, in my opinion.

And studies have shown that this type of thinking not only makes better investors but also results in better financial decisions.

What if there’s more to it than that?

What if the language you speak – and how it relates to the future – can make you a better investor and saver?

This is an idea that’s re-emerged over the past decade.

And because of my love of behavioral economics – like those championed by Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler – I’ve been intrigued by the idea.

Back in the 1930s, linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf developed the theory of linguistic relativity.

It’s all about how the structures of the languages we speak impact the way we see the world. The idea is that a person who grew up speaking, reading and writing English thinks differently about certain concepts than someone who grew up speaking, reading and writing Mandarin.

And it’s not cultural. It has to do with the way a language is structured.

Several years ago, behavioral economist Keith Chen revisited the idea of linguistic relativity. But he explored how it relates to our ability to save and plan for the future.

His question was this: If there’s no clear grammatical distinction between the present and the future, do speakers of that language view the future and the present differently?

For example, in English we say, “I will go to the play.”

English is a futured language. It forces us to divide time into tenses so that there’s a distinction between present and future events.

But in Mandarin you say, “I go to the play.”

It’s a futureless language. There’s no distinction between the present and the future.

Finnish is similar in that you essentially say, “Today be cold,” as well as “Tomorrow be cold.” The same tense is used whether you’re talking about the present or the future.

So how does that impact savings or potentially make you a worse or better investor?

Well, interestingly, after studying 76 developed and developing countries, Chen found that speakers of languages with a weaker future tense were actually better at preparing for the future…

And those results were after accounting for a variety of economic factors, as well as comparing households with the same income, religious beliefs, etc.

The only difference was language, even within the same country.

Chen found that speakers of futured languages – like English – had 39% less in assets for retirement. They were also less likely to save money in general, as well as more likely to adopt unhealthy habits.

Even in a country like Switzerland, where three languages are spoken, those who spoke one with a strong future tense saved only 36% as often as those who didn’t.

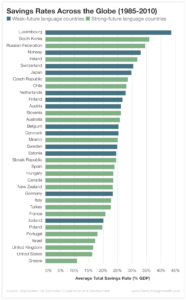

In the chart above, you can see the United Kingdom and the United States are at the wrong end of the savings graph. And they’re clustered with most of the other futured language speaking countries.

In contrast, Luxembourg, Norway, Switzerland, Japan and Finland – as well as the rest of the weak future tense speaking countries – had higher savings rates compared with GDP.

In those countries, Chen discovered that people gave the future the same weight as the present. And in turn, they planned accordingly.

Chen’s work with linguistic relativity has plenty of skeptics. But there is a point to be made here…

Don’t say, “I’m going to start saving for my retirement” or “I’m going to invest after the next sell-off.”

I know plenty of people who are guilty of using those grammatical crutches or excuses. They keep telling themselves that the future is some far-off place that they’ll get to eventually.

The problem is… that’s a lie.

It creeps closer and closer every single day.

The future should be given more importance than the present. And that goes double for financial decisions and investing.

Today, you should be focused on the future – and all the tomorrows ahead of you.

Good investing,

Matthew