Over the last several columns, I’ve examined how people get rich in this country… and why most people don’t.

The Federal Reserve announced earlier this month that U.S. household net worth just hit a record $100.8 trillion.

And in May, Spectrem Group reported that the number of U.S. households with a net worth of $1 million or more hit a record 11.5 million in 2017. (And if you include home equity, there are several million more.)

How did so many Americans become highly affluent?

Not through inheritance or trusts or special connections. And not – as many believe – by running a business either.

Thanks to the work of Dr. Thomas Stanley – who spent his career studying the values and habits of America’s affluent – we know that most followed a simple, straightforward formula.

They maximized their income, kept a sharp eye on their outgo, and religiously saved, invested and reinvested the difference.

Most people who could save don’t… or not nearly enough… or soon enough.

Yet saving is only the beginning. To achieve a high net worth, you need to invest that money and earn a high rate of return.

The best way to do that – especially if you’re starting small – is through common stocks.

Here’s how you can be sure…

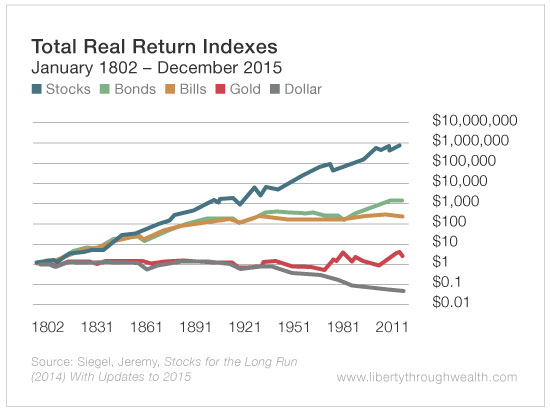

Dr. Jeremy Siegel – professor at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and author of Stocks for the Long Run – researched investment returns in the U.S. from 1802 to 2015.

What he discovered is nothing short of astonishing.

Over this period, the dollar declined – in inflation-adjusted terms – to less than $0.05.

A dollar invested in gold grew to $2.77 after inflation. Clearly, it’s better to hold a hard asset like gold than a depreciating asset like paper currency.

But it isn’t better than holding other liquid assets.

For instance, a dollar invested in Treasury bills over the period would have grown to $273 after inflation. In Treasury bonds, with the interest reinvested, it would have grown to $1,659.

But every dollar invested in a basket of common stocks – with dividends reinvested – would have turned into $1.3 million after inflation.

That’s right, every single dollar.

As the chart shows below, gold is not the great inflation hedge… stocks are.

Yes, there were plenty of market downturns and lots of neck-snapping volatility along the way. (That’s just the price of admission.) But history clearly demonstrates that nothing builds or preserves a fortune like a diversified portfolio of common stocks.

Or better yet, uncommon stocks that deliver market-beating returns.

Market novices are often scared of the stock market. They think of it as a casino. And, in truth, it often acts like one in the short term.

But over the long term, luck has little to do with it.

As Warren Buffett’s mentor Benjamin Graham pointed out, in the short term, the market is a voting machine. (Investors cast their votes through their buys and sells.)

But over the longer term, it is a weighing machine. And what it weighs is earnings.

As corporate profits increase, so do share prices.

It is impossible to consistently outguess the stock market in the short term. Millions have tried and failed.

I should mention one exception, however – a select group of people who are always in the market for the upswings and out for the downswings.

They’re called liars.

As Vanguard founder John Bogle likes to say, “Not only do I not know any successful market timers, I don’t know anybody who knows any.”

By now you should understand that nothing generates higher returns than common stocks… and nobody can tell you exactly when to be in the market and when to be out.

Does that mean you have to settle for average returns, the kind you might earn in an S&P 500 index fund?

Absolutely not.

In my next column, I’ll explain why… and what you should do instead.

Good investing,

Alex