In my last column, I explained why stocks should form the foundation of your long-term investment plan.

Over the past two centuries, nothing has performed better than a diversified equity portfolio – or even come close.

(If you’re skeptical, read my last column here.)

In some ways this is unremarkable…

Let’s say your kid or grandkid came to you for investment advice and said, “I have four investment possibilities. I can own gold. I can put my money in the bank. I can loan it out at interest. Or I can take an ownership stake in dozens of profitable businesses. What would you recommend?”

You’d advise the last choice, of course. (If not, you really have a lot of reading up to do.)

The first choice is the barbarous relic, a metal that accrues no interest, generates no earnings and pays no dividends.

The second is cash. The third is bond ownership.

And the fourth is a diversified equity portfolio. (Remember, stocks are not just electronic blips. They represent a fractional interest in a growing business.)

Most of us don’t have the time, the investment capital or the skills necessary to found and run a successful business. (My hat is off to those that do.)

And maybe that’s a good thing. Experience shows that the vast majority of new businesses fail in the first few years.

But virtually anyone can still own a piece of a thriving business through the quintessence of capitalism: the stock market.

With even a modest amount of money, an individual can accumulate a stake in any of thousands of the world’s greatest companies.

And it’s easy. A click of the mouse – a five-dollar commission – and you’re in. Another click – another five bucks – you’re out.

(Compare that with your typical real estate closing.)

And owning a piece of a public company is a whole lot simpler than running your own. You don’t have to take out loans, sign personal guarantees, hire or fire employees, grapple with an avalanche of federal mandates and regulations, pay lawyers and accountants, or even show up for work.

How great is that?

Some Americans today obsess over the issue of fairness. But the stock market shines here, too.

If you own shares of Amazon (Nasdaq: AMZN), for example, your gain over the next year will be exactly the same as that of the world’s richest man, Jeff Bezos.

Sure, he may own a few more shares than you do. But your percentage returns will be the same.

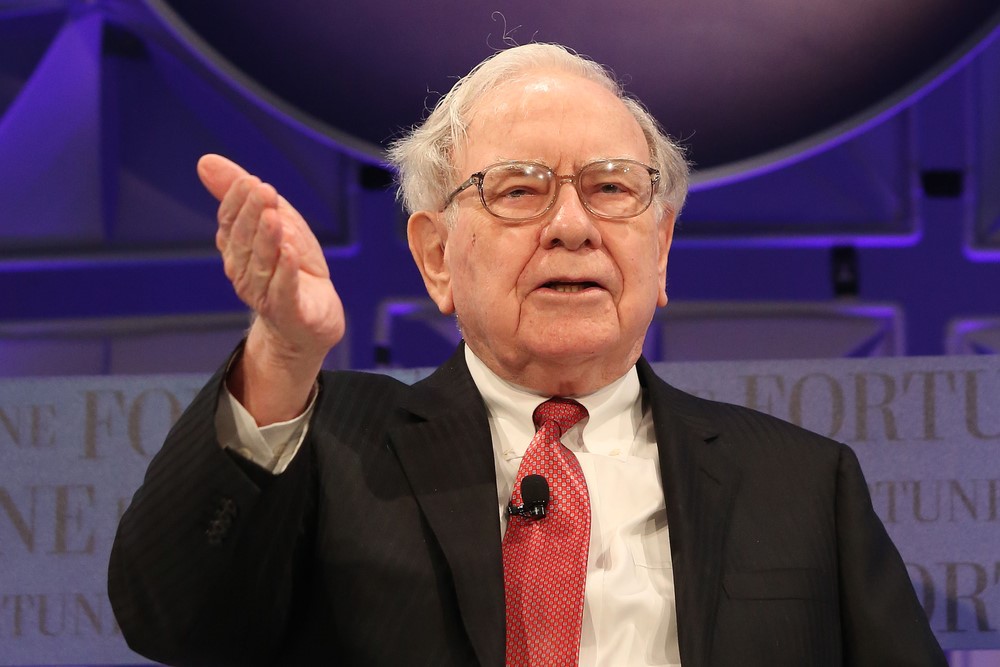

Warren Buffett has famously said that most investors would be fine just plunking their money in an S&P 500 index fund rather than picking individual stocks.

And I don’t disagree.

If you don’t have the time, the interest or the temperament to trade individual stocks, you don’t need to.

You can earn the return of the market averages and still do better over time than most investors in gold, cash or bonds.

But notice that Buffett hasn’t invested in an S&P 500 index fund himself.

That is why he’s one of the world’s richest men.

If you had invested $10,000 in the S&P 500 in 1964 – when Warren Buffett took the helm at Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK-A) – and reinvested the dividends, it would have grown to just over $1.7 million.

Not bad.

But the same amount invested in Berkshire Hathaway itself would have grown to more than $282 million.

That’s the difference between market performance and serious market outperformance.

I’m not suggesting that you are likely to repeat the performance of Berkshire’s CEO. (There’s only one Warren Buffett.)

But do you have a good shot at beating the S&P 500 in the months and years ahead?

If you know what you’re doing, absolutely.

The Wall Street Journal’s Mark Hulbert, the former editor of the independent Hulbert Financial Digest, confirmed that my investment letter The Oxford Communiqué beat the market for 16 consecutive years – and with far less risk than being fully invested in stocks.

In the weeks ahead, we’ll discuss exactly how.

Good investing,

Alex