- Emerging markets have seen impressive growth since 1988, but the trends have shifted recently.

- Today, Nicholas Vardy explains why emerging markets investing isn’t what it used to be.

I got my start in investing by focusing on global stock markets.

I still remember entering a bookstore in Amsterdam in 1992. There I picked up a book on the global investing philosophy of Sir John Templeton.

I learned that Templeton was a poor boy from Tennessee. His smarts took him to Yale University. Afterward, he won a Rhodes Scholarship to study at Oxford. He then made his fortune by investing in foreign stock markets where others feared to tread.

Like Templeton, I grew up in middle America. I also clawed my way to an elite education. And I too won fancy scholarships to study abroad.

It’s no surprise that I felt an immediate kinship with this pioneer of global investing.

To make a long story short… Four years after buying that book in Amsterdam, I was working in London as an emerging markets portfolio manager.

It was a heady time for global investing. Markets were soaring. Investing in red-hot emerging markets was all the rage.

Fast-forward to 2019, and the investment picture looks very different.

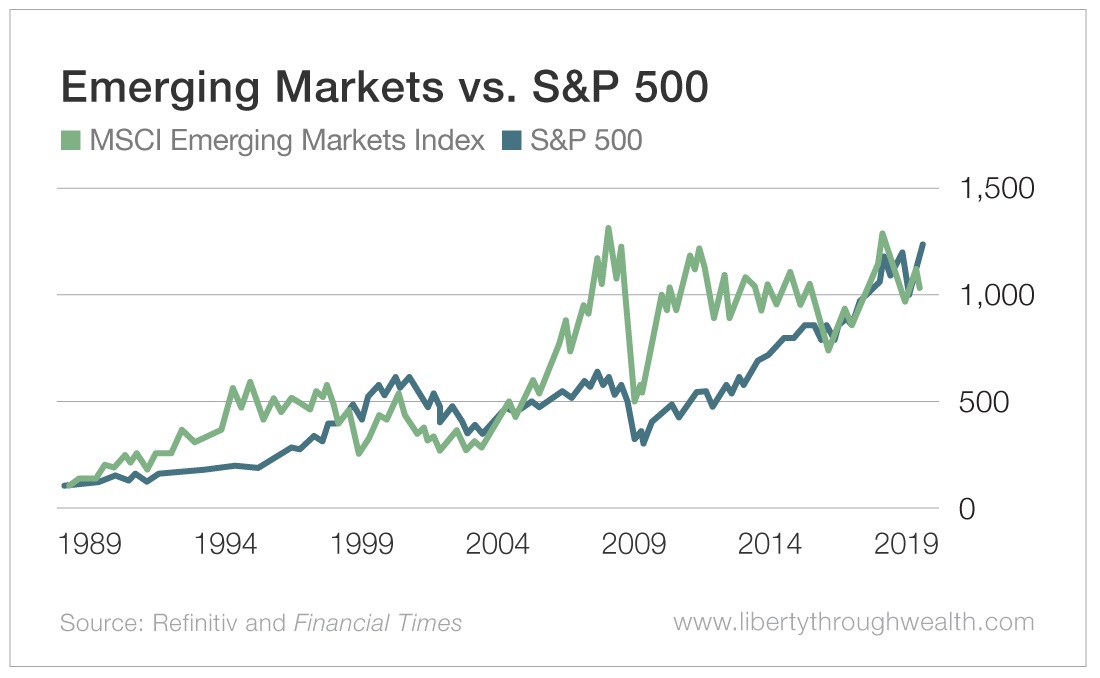

The last decade has been unkind to emerging markets investors. The MSCI Emerging Markets Index has yet to reach the highs it last saw in 2008.

And after two decades of crushing returns in developed stock markets, emerging markets are now underperforming the U.S. stock market.

This raises the uncomfortable question: Is emerging markets investing dead?

I can’t say for sure. But I don’t expect the heady days of the 1990s to return anytime soon.

Let me explain…

First, when emerging markets were new and sexy, the formula for making money was simple. Transfer ownership of state-owned enterprises to the private sector to reap enormous one-time gains. Wringing out inefficiencies afterward became much tougher.

The strong performance of emerging markets’ stocks between the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the global financial crisis in 2008 may have been a one-time historical moment. And that moment is now over.

Second, returns in emerging markets were boosted by the commodities boom. When commodity prices were soaring, the dynamics of growth were simple.

Russia sold oil to the world. Brazil sold iron ore to China. And China – the big kahuna of emerging markets – gobbled up everything that the big emerging markets could produce.

Today, economic growth in China has slowed to 6.2% – a level not seen in nearly three decades. And the outlook for natural resource-based emerging markets like Brazil and Russia has crumbled.

As Warren Buffett has observed, “It’s only when the tide goes out that you find out who’s been swimming naked.”

The Fallacy of Global Convergence

There is a third factor at play here that 99% of emerging markets investors ignore.

In The End of History and the Last Man, Francis Fukuyama argues that in a post-communism world, all countries would converge to Western-style free markets and liberal democracies.

As the cases of Putin’s Russia and Communist China confirm, Fukuyama turned out to be far too optimistic.

In his subsequent book Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity, Fukuyama makes a more realistic – and relevant – argument for investors.

Fukuyama compared a group of “low-trust societies” (France, southern Italy and China) with three “high-trust societies” (Japan, Germany and the United States).

His conclusion? Low-trust societies don’t work. High-trust societies do.

Drop your wallet in Switzerland, Norway or the Netherlands. Chances are it will be returned to you. Drop that wallet in China? Well, you can pretty much kiss it goodbye.

(Think about the implications of this for how companies treat their shareholders.)

Fukuyama also points out that there are different capitalisms in different places. Each version of capitalism is shaped by each place’s history and sociology. “Free markets” look very different in Africa, Latin America, Asia and formerly communist countries.

As a lawyer in central and eastern Europe, I helped privatize many state-owned enterprises. I learned this: Exporting Western laws to prior communist countries won’t turn them into prosperous capitalist democracies.

I also learned that investing in emerging markets based solely on conventional financial measures is naïve. Look at tried and true financial measures like price-to-earnings (P/E) and cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratios.

You will conclude that the U.S. stock market is overvalued compared with Russia, the Czech Republic or Greece. But to expect U.S.-style management, disclosure and profits from a Russian, Chinese or Greek company is foolish.

One decade of lagging performance may not condemn emerging markets to the dustbin of financial history. But I am far less optimistic than I was when I picked up that book on Sir John Templeton in Amsterdam.

Good investing,

Nicholas

P.S. I am rereading Harvard professor David Landes’ The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor. This classic work offers an invaluable historical perspective on emerging markets investing. Mitt Romney regularly quoted ideas from the book during his 2012 presidential campaign.