Some of the world’s leading investors preach the gospel of value investing.

Whether it’s Warren Buffett, Jeremy Grantham or David Einhorn, value investors represent the wisdom of looking at a stock as a share of a real business, the objectivity of focusing on hard numbers and the discipline of ignoring Mr. Market’s mood swings.

Yet, for all those investors who worship at the temple of value investing, there is an elephant in the room…

Over the past decade, value investing has not worked.

Want proof?

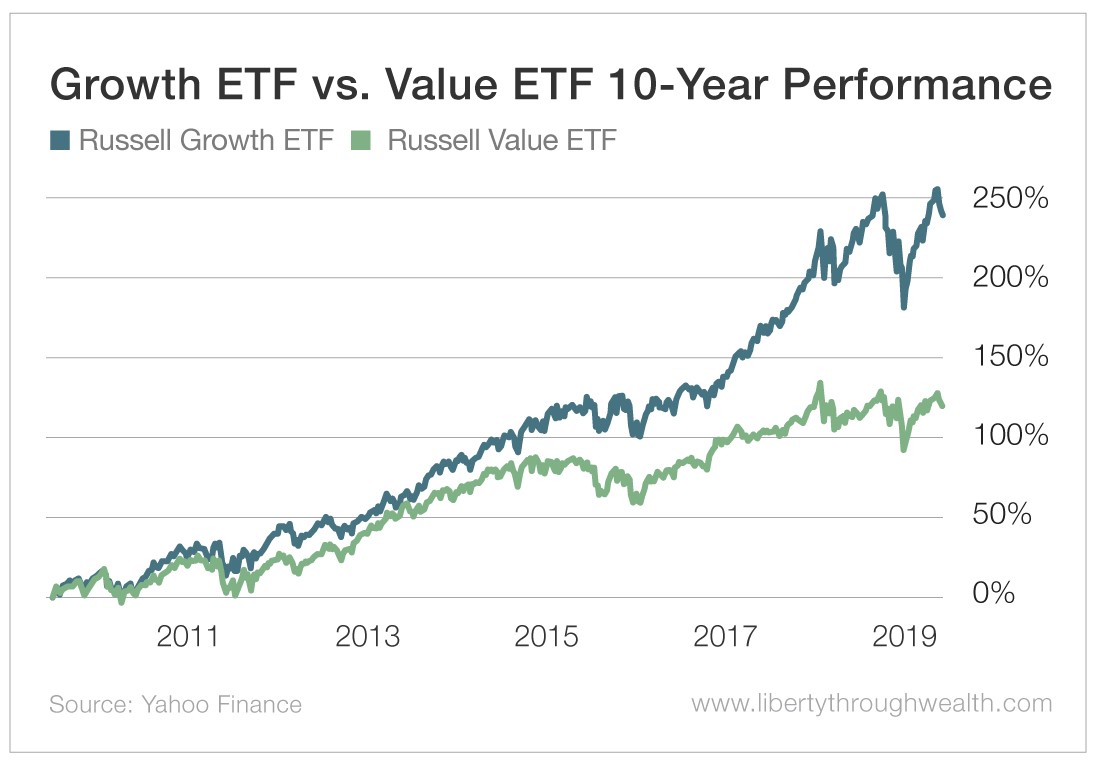

Just compare the returns of the iShares Russell Top 200 Value ETF (NYSE: IWX) with those of the iShares Russell Top 200 Growth ETF (NYSE: IWY).

Growth stocks have trounced value stocks by more than 2-to-1 over the past 10 years.

And, if anything, growth stocks’ outperformance is accelerating in 2019.

To be fair – whether they use measures like price-to-book, price-to-earnings or the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio – professional investors know that value investing isn’t a timing tool.

Still, over an entire decade, you’d think that the market would come around.

The trouble is… it hasn’t. And value investing’s badly lagging returns are starting to shake the faith of its most committed advocates.

Let me explain…

The Origin of Value Investing

Value investing boasts an impressive academic pedigree.

In Security Analysis, first published in 1934, Columbia professors Benjamin Graham and David Dodd offered an analytical framework for calculating a firm’s “intrinsic value.”

Remember, this was just five years after the speculative excesses and stock market crash of 1929.

Graham and Dodd’s framework gave investors the tools to assess whether a specific stock was cheap or expensive.

For example, a price-to-book value below 1 meant a company was trading below the value of its net assets – that is, its assets minus its liabilities.

With rare exceptions, that made the stock a buy. This approach worked well… until it didn’t.

On the Defensive

Today, value investors are on the defensive.

In fact, much of the investment research I read is written by a small army of academics and analysts attempting to explain away value’s lagging performance.

As each year passes, however, that is getting increasingly hard to do.

Their efforts remind me of the intellectual gymnastics used in Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica (1253) to reconcile newly rediscovered Aristotelian thought with medieval Christian doctrines.

It’s a courageous effort but all too unconvincing in the end.

Why Value Investing May Be Dead

Back in 2017, value investor David Einhorn reflected collective exasperation when he declared, “Value investing may be dead, and Amazon and Tesla killed it.”

Here’s why he may be right…

Value investing stems from an era when the hard, physical assets of companies mattered.

But this approach also means value investing has a blind spot. Sure, “book value” matters when you are looking at the value of cash, factories, tools and machinery in the 1930s.

But the value of many of the world’s most valuable companies in the 2010s doesn’t consist of hard assets.

After all, the value placed on software or intellectual property is just the product of an arbitrary accounting convention.

And the language of financial statement analysis ignores the value of, say, the “networking effects” of a Facebook (Nasdaq: FB) or Netflix (Nasdaq: NFLX).

The result?

Graham and Dodd’s approach values the most significant assets of today’s tech giants at zero.

Consider the example of Amazon (Nasdaq: AMZN).

For a company like Amazon, book value has been irrelevant to the stock’s performance.

Over the last five years, Amazon has never traded below 12 times book value. Today, it trades at 18.6 times its book value.

Had you decided not to invest in Amazon based on its high book value, you’d have made the same mistake that Warren Buffett did.

After all, over the past five years, Amazon’s share price has risen fivefold.

Nor is Amazon alone. The most successful investments of the past decade share the same characteristics.

Netflix trades at 27 times its book value. Facebook is a relative bargain, trading at six times its book value.

So should traditional value investing be consigned to the dustbin of history?

It’s probably too early to tell. After all, the four most dangerous words in investment are “This time it’s different.”

That said, it’s becoming clear that the holy book of value investing doesn’t offer all the answers. My own philosophy is to be flexible.

I’m happy to embrace any approach that works and to abandon anything that doesn’t.

As the economist John Maynard Keynes was reputed to say, “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

Good investing,

Nicholas